5 Critical Medical Battery Replacement Mistakes to Avoid

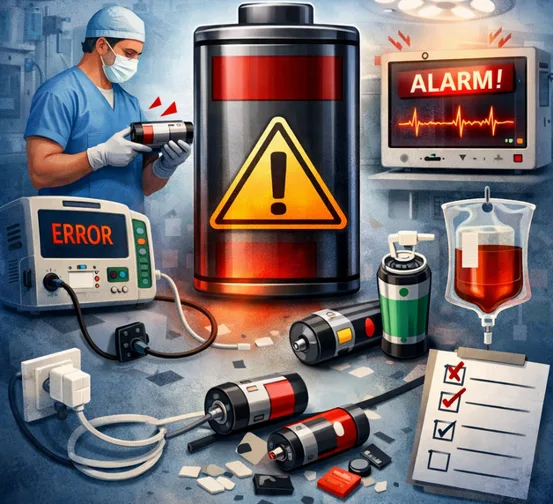

Medical devices are the backbone of modern healthcare. From infusion pumps to portable ventilators, these machines require constant, stable power. People often treat medical batteries like standard consumer electronics. This is a dangerous mistake.

In a clinical setting, a battery is a life-support component. A study by the FDA’s MAUDE database often cites battery failure as a top reportable event. These incidents frequently occur during patient transport or power outages. Reliability is not just a preference; it is a regulatory requirement.

Why Quality Standards Matter

Medical batteries must meet strict international standards like IEC 60601-1. This ensures the device remains safe under single-fault conditions. Using an uncertified battery bypasses these essential safety buffers. It puts the patient and the healthcare provider at unnecessary risk.

Hospital engineers often face pressure to cut costs. Third-party batteries seem like an easy way to save money. However, the “true cost” includes potential liability and shortened equipment lifespans. Genuine parts ensure the internal circuitry communicates correctly with the device.

The Complexity of Modern Power Cells

Modern medical batteries are rarely just “cells in a plastic box.” They contain complex Battery Management Systems (BMS). This internal board monitors voltage, temperature, and cycle counts. If the BMS is low-quality, the device may report 50% power when it is actually near zero.

Precision is the hallmark of medical technology. A sudden shutdown during a surgical procedure is a worst-case scenario. Understanding the common pitfalls of replacement is the first step toward prevention. We must prioritize “people-first” engineering over simple convenience.

Misunderstanding 1 – Assuming All Batteries are Created Equal

Many procurement managers view batteries as simple commodities. They believe a battery with the same dimensions and voltage is a perfect match. This logic works for a household flashlight but fails in a clinical environment. Medical-grade batteries undergo rigorous testing that consumer cells never face.

The Myth of “Universal” Compatibility

A battery might fit into a slot without being compatible. Medical devices require specific discharge rates to function during peak loads. For example, a defibrillator needs a massive burst of energy in seconds. A generic battery may collapse under this high-current demand.

Standard lithium-ion cells vary greatly in chemical stability. High-end medical cells use specific stabilizers to prevent thermal runaway. Using a “knock-off” brand increases the risk of fire or chemical leaks. These hazards are unacceptable in an oxygen-rich hospital room.

Differences in Capacity and Cycle Life

Real-world data shows that “equivalent” batteries often underperform. A genuine manufacturer battery might provide 500 full charge cycles. In contrast, a low-cost alternative may degrade after only 200 cycles. This leads to more frequent replacements and higher long-term labor costs.

| Feature | Medical-Grade Battery | Consumer/Generic Battery |

| Safety Standard | IEC 62133 Certified | Variable/Uncertified |

| Discharge Rate | High-Current Optimized | Low/Standard |

| BMS Intelligence | Real-time Data Logging | Basic Protection Only |

| Housing | Flame-retardant (UL94-V0) | Standard Plastic |

The “Smart” Battery Gap

Most modern devices use “smart” technology to track battery health. These batteries communicate via SMBus or I2C protocols. Generic replacements often lack the correct firmware to talk to the device. The machine may show a “Battery Error” even if the cells are full.

This communication gap prevents the device from predicting its remaining runtime. A nurse might see three bars of power, yet the device dies moments later. True expertise in medical maintenance requires recognizing these invisible technical barriers. Always verify that the replacement part matches the exact OEM specifications.

Misunderstanding 2 – Overlooking Calibration and Software Sync

A common error among technicians is the “plug and play” mentality. They assume that once a new battery is physically connected, the job is done. However, modern medical devices are driven by complex software. This software must be “taught” the characteristics of the new power cell.

The Problem of “Ghost” Power Readings

The device’s internal “fuel gauge” relies on historical data from the old battery. If the old battery was degraded, the software might still expect low performance. This leads to “ghost” readings, where a device shows 100% charge but shuts down minutes later.

This discrepancy occurs because the Battery Management System (BMS) hasn’t reset its internal “Full Charge Capacity” (FCC) marker. Without calibration, the software remains out of sync with the hardware. In a critical care unit, an inaccurate runtime estimate is a liability.

Why Calibration is a Requirement

Calibration is the process of setting new “empty” and “full” flags for the BMS. For many lithium-based medical batteries, this requires a specific cycle:

- Charge the new battery to a true 100% capacity.

- Rest the battery for 2+ hours to let the chemistry stabilize.

- Discharge the battery completely in a controlled manner.

- Recharge it fully to “lock in” the new capacity data.

This routine resets the “Max Error” bit in the software. Research shows that uncalibrated smart batteries can have a measurement error of over 10%. Regular calibration, typically every three months or after 40 cycles, maintains this vital accuracy.

Syncing with the Device Firmware

Some high-end ventilators and infusion pumps require a manual reset via the service menu. Technicians must often enter a “Battery Replaced” command. This clears the cycle count and life-expectancy logs.

| Calibration Step | Purpose | Critical Note |

| Full Discharge | Identifies the true “zero” point | Do not interrupt once started. |

| Equilibrium Rest | Stabilizes internal voltage | Essential for accurate sensing. |

| Cycle Reset | Clears history of the old battery | Prevents false aging alarms. |

Failing to perform these software steps can void warranties. It may also trigger “service required” lights prematurely. True expertise involves managing the digital life of the battery just as much as the physical one.

Misunderstanding 3 – Neglecting Storage and Environmental Factors

Many facilities treat battery storage like stationery supplies. They buy in bulk and stack boxes in a warm closet. This “set it and forget it” approach is a silent killer of battery health. Temperature and state of charge during storage significantly impact a battery’s total lifespan.

The Chemical Cost of Heat

Heat is the primary enemy of lithium and nickel-based chemistries. According to the Arrhenius equation, chemical reactions double for every 10∘C increase in temperature. Storing batteries in a room at 30∘C (86∘F) accelerates internal degradation.

Medical batteries should ideally be kept in a climate-controlled environment at 15∘C (59∘F). High temperatures cause the electrolyte to break down. This creates internal resistance, reducing the battery’s ability to deliver power during peak medical procedures.

The “Deep Discharge” Trap

A battery is never truly “off.” Internal circuits and self-discharge slowly drain the cells even when sitting on a shelf. If a battery’s voltage drops below a certain threshold, the BMS may “lock” the battery for safety.

Pro Tip: Never store a medical battery at 0% or 100% for long periods. The “sweet spot” for long-term storage is typically 40% to 50% charge.

When a battery enters a “deep discharge” state, the copper current collectors can dissolve. This creates a permanent internal short circuit. Attempting to charge a battery in this state can lead to overheating or venting.

Environmental Checklist for Facilities

Facilities should implement a “First-In, First-Out” (FIFO) inventory system. This ensures that no battery sits idle for more than six months. Use the following table to audit your storage practices:

| Factor | Ideal Condition | Risk of Neglect |

| Temperature | 10 C – 20 C | Permanent capacity loss |

| Humidity | 45% – 75% (non-condensing) | Corrosion of terminals |

| Charge Level | 40% – 60% capacity | Cell “sleep” or bricking |

| Rotation | 6-month inspection | Expired warranty/shelf life |

Moisture and Contamination

Hospitals are high-moisture environments due to frequent cleaning. If storage areas are near sterilization centers, humidity can corrode the gold-plated contact pins. This corrosion increases electrical resistance, which generates heat during use.

Always keep replacement batteries in their original anti-static packaging. This protects the sensitive internal logic boards from static discharge (ESD). Proper storage is not just about organization; it is about preserving the chemistry of life-saving power.

Misunderstanding 4 – Using Generic Chargers for Specialized Cells

In an effort to streamline equipment, some technicians use “universal” chargers. They assume that if the plug fits, the power is compatible. This is a critical misunderstanding of how medical battery chemistry functions. A charger is not just a power supply; it is a sophisticated controller.

The Precision of Charging Profiles

Medical batteries require specific charging algorithms, such as Constant Current/Constant Voltage (CC/CV). A generic charger may not transition between these stages at the correct millivolt threshold. Even a slight overcharge can lead to “plating,” where lithium metal forms inside the battery.

This internal plating significantly increases the risk of a thermal event. Conversely, undercharging prevents the battery from reaching its full chemical potential. This leaves the medical device with less “run-time” than the manufacturer intended.

Communication and Safety Handshakes

Genuine medical chargers communicate with the battery’s internal BMS. They check for cell balance and internal temperature before applying a full load. A generic charger lacks this “handshake” capability. It will continue to force current even if a cell is overheating.

Most medical-grade chargers also include a “maintenance mode.” This mode uses a pulse-charging technique to prevent sulfation in lead-acid batteries or dendrite growth in lithium ones. Generic adapters provide a “dumb” steady stream of power, which can bake the battery’s internal components over time.

The Hidden Risks of Incorrect Voltage

Even a 0.1V difference in charging voltage can reduce a battery’s life by hundreds of cycles. High-quality chargers are calibrated to tight tolerances (often within ±1%). Cheap alternatives can fluctuate by as much as 5%, causing erratic charging behavior.

Why “Fast Charging” Isn’t Always Better

Technicians often favor fast chargers to get equipment back in service quickly. However, rapid charging generates significant internal heat. For medical batteries, “slow and steady” usually leads to a much longer service life.

Always use the charger specified by the original equipment manufacturer (OEM). If you must use a third-party charger, ensure it is medically certified and specifically mapped to the battery’s part number. Reliability starts at the wall outlet.

Misunderstanding 5 – Delaying Replacement Until Total Failure

In many high-pressure clinical environments, the “if it isn’t broken, don’t fix it” mentality prevails. This is perhaps the most dangerous misunderstanding regarding medical batteries. Waiting for a battery to reach zero capacity before replacing it is a reactive strategy. In healthcare, success depends on proactive maintenance.

The “Sudden Death” Phenomenon

Lithium-based batteries do not fail linearly. They often maintain a seemingly healthy voltage until they hit a “cliff.” Once the internal resistance reaches a critical point, the voltage can collapse instantly under load.

A device may appear functional while plugged into AC power. However, during a patient transfer, the battery must take over the full load. If the battery is aged, the sudden current draw can cause an immediate system shutdown. This “sudden death” during transport is a leading cause of adverse patient events.

Understanding the “End of Life” (EOL) Metric

Medical manufacturers define the “End of Life” for a battery long before it hits 0% capacity. Usually, a battery is considered failed when it can only hold 80% of its original rated capacity.

At 80% capacity, the internal chemistry is no longer stable enough to guarantee the “Reserve Run Time.” This reserve is the safety margin required for emergency situations. Using a battery beyond this 80% threshold is like driving a car with a failing fuel pump; it might work today, but it will fail when you need it most.

The Cost of Procrastination

Delaying replacement doesn’t actually save money. Aged batteries can swell as they off-gas, a process known as “outgassing.” A swollen battery can exert hundreds of pounds of pressure on the internal frame of an infusion pump or monitor.

- Physical Damage: Swelling can crack high-precision circuit boards or LCD screens.

- Labor Costs: Extracting a stuck, swollen battery takes significantly more technician time.

- Downtime: A ruined device shell requires expensive factory repairs, costing far more than a simple battery.

Implementing a Scheduled Replacement Program

Top-tier hospitals use a “Life Cycle Management” (LCM) approach. Instead of waiting for failure, they replace batteries based on two metrics:

- Chronological Age: Typically every 24 to 36 months, regardless of use.

- Cycle Count: Replacing after a specific number of discharges (e.g., 300 cycles).