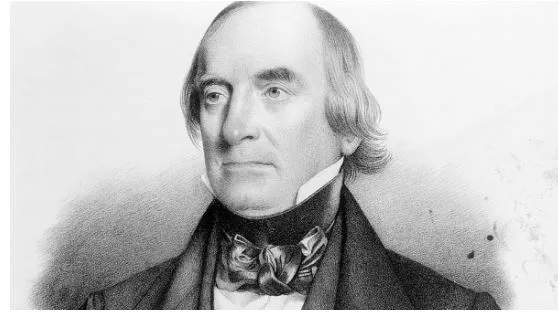

Charles Stewart: The Sailor Who Spanned Eras of a Growing Navy

When the U.S. Navy’s history is told, we often hear about great sea battles, famous captains, and dramatic moments. Charles Stewart lived through many of those moments—and many more that rarely get noticed. Born in Philadelphia in 1778, just after British forces evacuated the city, Stewart grew up in a precarious world. His father died when he was young; his mother had few resources. At age thirteen, he went to sea as a cabin boy. That youthful entry into seafaring was dangerous, basic, uncertain—but it built in him endurance, adaptability, and a commitment to maritime duty that lasted six decades.

Stewart’s earliest years in uniform came during the Quasi-War with France. As a lieutenant, he served aboard frigates hunting privateers, overseeing outfitting, recruiting, and challenging conditions. He commanded the schooner Experiment, capturing French vessels, freeing American ships seized under dubious claims, and—in one incident—rescuing nearly seventy women and children from a vessel wrecked on a reef just before it sank. Small acts in remote places, but ones that showed the dual role of a Navy officer in that era: war fighter and humanitarian.

During the Barbary Wars, Stewart showed how emerging U.S. sea power could protect its citizens, deter piracy, and build respect abroad. Commanding brig Sirlen (or Siren) in the Mediterranean, he helped maintain the blockade of Tripoli, participated in shore assaults, and saw what naval diplomacy and firepower looked like when both had to be used carefully. Those early years shaped his view that readiness, discipline, and clear rules mattered; a ship’s log, its crew’s conduct, its adherence to orders—all anchored more than individual courage.

His name is often associated with the USS Constitution (“Old Ironsides”) during the War of 1812. As its captain, Stewart carried out two successful cruises between 1813 and 1815. He led Constitution when it captured HMS Cyane and HMS Levant (February 20, 1815)—a double capture from one American frigate, a rare feat. Importantly, the Treaty of Ghent had already been ratified by the United States three days before, but word had not yet reached the combatants; the victory still lifted morale, affirmed U.S. naval presence, and secured Stewart’s reputation as a steady, bold commander.

But Stewart’s life wasn’t simply a string of victories. After the War of 1812, the Navy’s demands shifted. Peace times, budget cuts, refits, rotations: officers were forced to adapt. Stewart commanded squadrons in the Mediterranean, then in the Pacific. He had to manage diplomatic tensions (for example, with foreign powers and local authorities), supply logistics across vast oceans, and the morale of sailors in remote posts. He presided over years when the U.S. Navy itself was still defining what good maintenance, what good leadership, and what good discipline meant. Those quieter years shaped the institutional Navy far more than single battles often do.

There were controversies. Stewart was court-martialed in the 1820s after an incident involving his treatment of subordinate officers and decisions in a diplomatic-naval tension in South America, especially around blockades and neutral rights. The affair was highly publicized, his reputation was questioned, and his personal life was also affected (his marriage ended in divorce). But he was acquitted. That episode, though painful, seems to have reinforced for him that command involves risk—not just from enemies but from politics, interpersonal conflict, and moral dilemmas. Accepting responsibility (or at least being prepared to face criticism) seems part of his character.

Stewart’s later career included oversight roles: Naval Commissioner, command of the Philadelphia Navy Yard at various periods, and senior flag officer status in 1859. He remained on active duty until 1861, retiring only when age and the national crisis (Civil War looming) made continued command untenable. He was promoted to rear admiral on the retired list in 1862. Furthermore, he died in 1869, aged 91. His long life spanned from the earliest stirrings of the Navy after the Revolutionary War, through sail-powered frigates, through steam beginnings, to an America on the brink of industrial naval modernization.

What does Stewart teach us today, especially on a day honoring veterans and naval tradition? First, that courage isn’t always visible. It shows up in nights at sea under sail, in storms, in dangerous supply missions, in diplomacy on foreign coasts. Second, that integrity and moral judgment matter as much as tactical success. Stewart’s willingness to stand trial rather than deflect blame, to work under uncertain orders, to face mistakes—even in an era with delayed communication and imperfect intelligence—is a model of leadership that resists easy mythologizing. Third, readiness must be constant. He served during times of peace and war, yet was always prepared when conflict came. The Navy’s strength, then as now, comes from those who maintain vigilance, discipline, and skill even when waves are calm.

Finally, Stewart’s legacy reminds us that long service matters. Decades of command, of quiet work, of mentorship (to junior officers, to shipbuilders, dockyard workers), of maintaining standards in non-glamorous roles—all contribute to what naval power really is. On Navy Birthday, we salute not just the captains of famous frigates, but those whose steady hands kept ships seaworthy, whose judgments in less dramatic circumstances made possible those dramatic moments.