When to Use Self-Drilling Bars or DTH Bits in Complex Geology

The real challenge: complex geology rarely allows neutral decisions

Anyone who has worked in unpredictable geology knows how quickly conditions can shift. A hole that starts cleanly may collapse within minutes. Groundwater sometimes arrives earlier than expected, or fractured layers behave differently from the geotechnical report.

As one experienced engineer put it, “The ground doesn’t always behave the way the plan says it should.” And in these situations, the choice between self-drilling bars and DTH systems often determines whether a job moves forward smoothly or stalls. These tools are not interchangeable; they address different geological challenges and risk profiles.

What follows is a practical, field-informed overview of how engineers typically decide which system is appropriate—not based on catalog descriptions alone, but on ground behavior, project demands, and the lessons repeatedly learned on job sites.

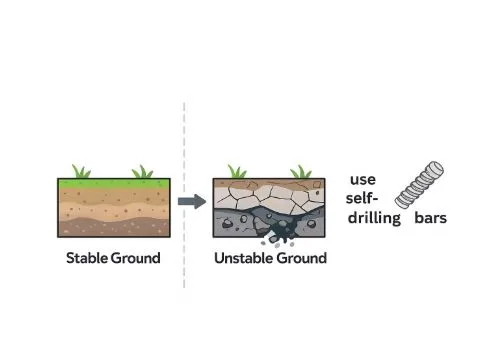

When drilling and ground support must happen together (Self-Drilling Bars)

In many loose, fractured, or collapsing formations, the primary challenge is not penetration but keeping the hole stable long enough to complete drilling. Under these conditions, even short sections of unsupported open hole can deteriorate quickly.

Systems such as self-drilling bars are commonly applied in these environments. Their hollow-core design allows drilling, grouting, and anchoring to occur in sequence without removing the drill string. This combined approach helps reduce the likelihood of collapse in weak or unconsolidated ground and is widely used in slopes, tunnels, retaining structures, and micropile applications.

In the words of one field supervisor: “If the ground won’t stand long enough for a second step, you combine the steps.”

This reflects a common rationale for selecting self-drilling systems in unstable formations.

Field indicators that often suggest SDB is appropriate

While geotechnical reports provide foundational information, experienced crews frequently rely on early-site observations to determine whether self-drilling bars may be suitable. Indicators often include:

- The collar loosens or erodes during setup

- Cuttings appear waterlogged, loose, sandy, or mixed with fines

- Flushing pressure becomes unstable

- The bit hesitates or binds under light feed pressure

- Groundwater enters at shallow depths

- The formation shows visible fracturing or blocky movement

These signs do not guarantee that self-drilling bars are required, but they commonly appear on projects where SDB ultimately proves to be the more efficient and reliable option. Attempting conventional drilling in such conditions may increase the likelihood of interruptions or additional stabilization work.

When deep, straight holes in hard or abrasive rock are the priority (DTH systems)

Not all complex geology involves instability. Some formations are highly competent but extremely hard or abrasive, making penetration and hole straightness the primary challenges. In these cases, energy delivery at the bit becomes more important than ground support.

This is where DTH systems tend to perform well. With the hammering action placed directly behind the bit, DTH reduces energy loss over long distances and maintains stable progress in dense rock types such as granite, basalt, and quartzite.

Working with a dependable DTH bits manufacturer also provides access to different face designs—flat, concave, convex—that are selected based on expected rock behavior and the desired balance between penetration rate and hole straightness.

One driller described the logic this way: “In hard rock, consistent energy at the bit matters more than anything else.”

That principle reflects why DTH is frequently chosen for deep drilling, blast holes, geothermal wells, and other straightness-critical applications.

A practical decision chain engineers often use in the field

Rather than relying solely on equipment specifications, many teams use a set of quick, experience-based questions to determine which system fits the geology and project needs:

1. Can the ground maintain a stable open hole?

- If not, self-drilling bars are commonly evaluated first

- If yes, further assessment continues

2. Does the project require significant depth or strict straightness?

- If yes, DTH is often a strong candidate

- If no, evaluate support requirements

3. Does the formation require immediate reinforcement?

- If yes, SDB tends to be preferred

- If no, either system may be viable depending on conditions

4. Is the rock extremely hard or abrasive?

- If yes, DTH is frequently selected

- If no, consider the impact of groundwater and collapse risk

This framework does not replace detailed geological evaluation, but it reflects a practical approach widely used to minimize avoidable issues in the early stages of drilling.

What commonly happens when the selection doesn’t match the geology

Mistakes in choosing between SDB and DTH do not necessarily result in immediate failure, but they often create compounding problems:

- Using DTH in unstable, loose, or collapsing layers can increase the risk of stuck tools or incomplete holes

- Using SDB in extremely hard rock may accelerate wear on sacrificial bits and slow progress

- Improper flushing in either system can cause overheating and premature bit damage

- Selecting an unsuitable DTH face design may lead to hole deviation

- Using incompatible threads within a drill string can introduce vibration and increase component wear

These outcomes are consistent with challenges frequently reported in field operations and tend to increase both time and cost when they occur.

Practical recommendations for more reliable results in complex geology

Successful drilling in complicated formations often depends on how early observations are handled. Running a short test hole when conditions are uncertain, adjusting flushing settings based on real-time feedback, and choosing tools aligned with the project’s primary risk—whether collapse, depth, hardness, or straightness—can significantly improve outcomes.

In many projects, it is not the complexity of the geology itself but the mismatch between ground behavior and the chosen system that leads to trouble. A clear decision-making approach, supported by both geotechnical data and field observations, is one of the most dependable ways to reduce unexpected setbacks.