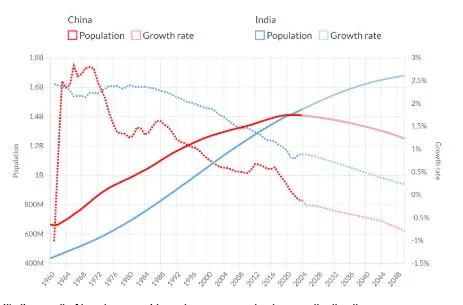

India Expected to Add 200M by 2050, China to Lose 100M

In April 2023, India overtook China as the world’s most populous country, with 1.43 billion people compared to China’s 1.41 billion.

That two percent difference already reflects a major demographic turning point, and over the next 30 years it will widen into a structural shift that reshapes labor markets, economic growth, and geopolitical influence across Asia and the global economy.

By 2050, India is projected to add more than 200 million people, while China is expected to lose over 100 million, according to UN-aligned estimates summarized by GeoRank.

It’s the result of two demographic systems now moving in opposite directions.

Why does that matter?

Because population size matters far less than population structure, and China and India now sit at opposite ends of the global age spectrum.

The Fertility Gap That Changed Everything

China’s Birth Rate Collapse

China’s fertility rate fell to about 1.0 births per woman in 2023, far below the replacement level of 2.1.

That puts China among the lowest fertility countries in the world, alongside South Korea and parts of Southern Europe.

In absolute terms, China recorded roughly 9 million births in 2023, down from 18 million in 2016 and over 25 million in the late 1980s.

The speed of this decline is historically unusual.

Even after the formal end of the one-child policy in 2016, fertility didn’t rebound.

It continued falling as housing costs rose, urbanization accelerated, and female education expanded.

In 1980, fewer than 20 percent of Chinese lived in cities; by 2023, that figure exceeded 65 percent, and urban fertility everywhere is lower.

Key drivers of China’s low fertility include:

- Median first marriage age rose above 29 years.

- Urban housing prices reached over 20 times annual income in top cities.

- Female tertiary education enrollment exceeded 60 percent.

- Childcare costs rose faster than wages for a decade.

Each factor matters alone, but together, they make large families economically irrational for most urban households.

India’s Slower, Uneven Decline

India’s fertility rate has also fallen sharply, but it hasn’t collapsed.

In 2000, India averaged about 3.3 births per woman. By 2023, it had fallen to roughly 2.0, just below replacement.

That average hides variation.

Southern states such as Kerala and Tamil Nadu have fertility rates near 1.6, similar to Europe.

Northern states such as Bihar and Uttar Pradesh remain above 2.5.

This regional diversity gives India demographic momentum China no longer has.

In raw numbers, India recorded around 23 million births in 2023, more than double China’s total.

Even if India’s fertility continues declining, its large cohort of young adults guarantees population growth through at least the 2040s.

Age Structure Is the Real Divider

China Is Already an Aging Society

China’s median age reached 40.6 years in 2025. That’s up from 32 in 2010 and 22 in 1980. The change happened in less than two generations.

By contrast, the United States sits at 39.3, and India at 29.5.

China’s old-age dependency ratio tells the story more starkly. In 2000, there were about 10 people aged 65+ for every 100 working-age adults. By 2023, that figure exceeded 21. By 2050, it’s projected to exceed 40.

This means:

- Fewer workers support more retirees.

- Pension and healthcare costs rise mechanically.

- Economic growth must rely on productivity, not labor expansion.

No policy tweak reverses that arithmetic.

India Remains Young, For Now

India’s median age of 39 makes it one of the youngest large economies.

65 percent of its population is under 35, compared to less than 40 percent in China.

India adds around 10 million people to its working-age population every year, while China loses about 5 million.

This creates what economists call a demographic dividend.

If jobs exist, a larger share of the population produces rather than consumes.

But dividends aren’t automatic. India must absorb those workers into productive employment, or the advantage becomes a liability. Youth unemployment in India already exceeds 20 percent in urban areas, highlighting the risk.

Labor Markets Are Moving in Opposite Directions

China’s labor force peaked around 2015 at roughly 940 million people. By 2023, it had already shrunk by more than 40 million. By 2035, projections suggest another decline of 70 to 100 million.

That shift explains several recent trends:

- Rising factory wages despite slowing growth.

- Rapid automation in manufacturing.

- Increased offshoring of labor-intensive production.

India’s labor force, by contrast, continues expanding.

It stood near 520 million in 2023 and is projected to exceed 650 million by 2040.

But labor quality matters as much as quantity.

China’s average worker has about 11 years of schooling.

India’s average is closer to 7.

China produces roughly twice as many STEM graduates annually despite a smaller youth cohort.

So the comparison isn’t simply young versus old.

It’s young with lower skills versus aging with higher skills.

Urbanization and Family Economics

Urbanization shapes fertility everywhere.

China’s rapid urban transition compressed three centuries of demographic change into four decades.

Urban couples face high opportunity costs for childbearing, especially women.

As a result, over 70 percent of Chinese births now occur to parents over age 30.

India’s urbanization rate is about 36 percent, barely half of China’s.

Rural households still account for a large share of births, where children contribute economically earlier.

That won’t last forever.

As India urbanizes, fertility will continue falling.

The difference is timing.

China aged before it became rich.

India is aging more slowly, buying time to raise incomes before dependency pressures peak.

Geopolitical and Economic Consequences

Demographics don’t determine power, but they shape options.

China’s shrinking workforce constrains long-term growth potential.

Most estimates place China’s sustainable growth rate below 4 percent by the 2030s, down from over 8 percent in the 2000s.

An older population also shifts fiscal priorities toward pensions and healthcare rather than infrastructure or defense.

India’s growing population supports higher potential growth, often estimated near 6 percent if reforms continue.

A larger domestic market attracts investment even when global trade slows.

But size cuts both ways.

A younger population raises demands for housing, jobs, water, and energy.

Failure to meet them risks social instability rather than growth.

What the Projections Get Wrong

All demographic projections share one weakness.

They assume behavior changes slowly.

China could see a modest fertility rebound if housing costs fall and childcare expands, but moving from 1.0 to even 1.5 would be historically large.

India could see faster fertility decline if female education and urbanization accelerate.

Migration also matters.

China remains largely closed to immigration. India exports labor but doesn’t import it. Neither is likely to use migration as a demographic lever at scale.

The Long View

China is entering a period of demographic contraction that will last decades.

India is entering a window of demographic opportunity that will eventually close.

China’s current economic slowdown is often framed around real estate stress or technology restrictions, yet its working-age population has been shrinking since the mid-2010s.

India’s growth narrative is frequently tied to reforms or foreign investment, even though its labor force expands by roughly 10 million people each year regardless of policy shifts.

Much of today’s public debate is anchored in immediate events. Quarterly growth numbers, election cycles, trade disputes, and short-term policy shifts dominate headlines and shape perception. These signals feel urgent because they change quickly and offer clear narratives.

But demographics quietly set the boundaries inside which policy, economics, and geopolitics operate.