Prevent Errors in Small Signal Transistor Circuit Design

Small signal transistors form the backbone of modern electronics, quietly enabling precision in audio amplifiers, sensor conditioning circuits, RF front-ends, and countless analog interfaces. Despite their ubiquity, these components are frequently misunderstood, leading to design errors that cascade into costly failures. Engineers routinely encounter oscillations that render amplifiers unusable, distortion that corrupts signal fidelity, thermal runaway that destroys prototypes, and inexplicable circuit failures that delay product launches. These problems often stem not from component defects but from preventable design oversights—incorrect biasing, inadequate frequency compensation, poor layout practices, or mismatched impedances. This article provides electrical engineers with a practical, actionable framework to identify, avoid, and correct the most common pitfalls in small signal transistor circuit design. By applying systematic analysis, rigorous component selection, and proven design techniques, you can achieve reliable performance from your first prototype, eliminating the frustration and expense of repeated design iterations.

Understanding the Core Role of Small Signal Transistors

Small signal transistors are semiconductor devices optimized for amplifying, switching, or impedance matching in low-power analog circuits where signal fidelity and precision matter most. Unlike power transistors designed to handle substantial currents and voltages, or Power MOSFETs built for efficient switching in high-power applications, small signal transistors operate in the milliwatt to low-watt range, focusing on linearity and frequency response rather than raw power handling. Their primary function is to amplify weak electrical signals—from microvolts to a few volts—without introducing significant distortion or noise. In audio preamplifiers, they boost microphone signals; in sensor interfaces, they condition low-level transducer outputs; in RF circuits, they provide gain in the front-end stages. Three parameters define their performance: hFE (current gain, typically 100–400) determines how effectively a small base current controls collector current; fT (transition frequency, ranging from tens of MHz to several GHz) sets the upper limit for useful amplification; and noise figure quantifies how much the transistor degrades signal-to-noise ratio. Misunderstanding these specifications leads directly to design failures—choosing a transistor with insufficient fT causes roll-off at operating frequencies, while ignoring noise figure ruins sensitive receiver circuits. Mastering these fundamentals is your first line of defense against preventable errors.

Top 5 Common Circuit Design Errors and Their Impact

The first and most pervasive error is incorrect biasing, where engineers miscalculate the DC operating point, forcing the transistor into cutoff (no collector current flows) or saturation (behaving like a closed switch rather than an amplifier). This manifests as severe signal clipping, zero gain, or complete loss of amplification. Second, ignoring the Miller effect—the multiplication of base-collector capacitance by voltage gain—causes unexpected high-frequency roll-off and potential oscillation in multistage amplifiers. Designers who neglect fT find their 100 MHz transistor unusable at 50 MHz due to phase shift accumulation. Third, inadequate thermal analysis leads to catastrophic failures: even small signal devices dissipating 200–500 mW can experience thermal runaway if ambient temperature rises or heat sinking is absent, causing hFE to drift and bias points to shift unpredictably. Fourth, improper impedance matching between stages creates gain loss, reflections in RF circuits, or unstable feedback loops that trigger parasitic oscillations at unexpected frequencies. Finally, overlooking parasitic capacitance and PCB layout effects—long base leads acting as inductors, ground loops injecting noise, or inadequate decoupling—transforms a theoretically sound schematic into a dysfunctional prototype. Each error compounds during integration, turning minor oversights into project-delaying failures that demand complete redesigns.

Case Study: Biasing Blunders in an NPN Amplifier Stage

Consider a common-emitter NPN amplifier designed for 10x voltage gain at 10 kHz. In the flawed version, the designer uses a stiff voltage divider (low resistor values) to set base voltage at 2.5V, assuming Vbe = 0.7V will yield 1.8V across the emitter resistor. However, temperature variations shift Vbe by –2mV/°C; a 50°C rise reduces Vbe to 0.6V, increasing collector current by 50% and pushing the transistor toward saturation. The corrected design introduces a larger emitter resistor (1kΩ instead of 100Ω) to provide negative feedback: as collector current increases, emitter voltage rises, reducing Vbe and stabilizing the operating point. Additionally, the base bias resistors are increased to reduce loading while maintaining adequate base current. This simple modification—emitter degeneration—ensures the bias point remains stable across temperature and component tolerances, preventing distortion and maintaining consistent gain.

Selecting the Right Transistor: A Data-Driven Approach for Engineers

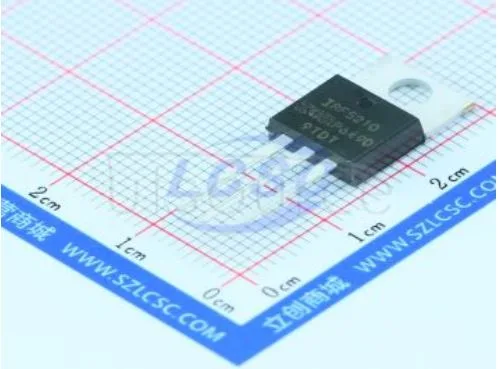

Effective transistor selection begins with a rigorous specification of circuit requirements: maximum collector-emitter voltage, peak collector current, operating frequency range, acceptable noise figure, and power dissipation limits. Once these parameters are defined, compare BJT versus FET topologies—BJTs offer higher transconductance and lower noise at audio frequencies, making them ideal for precision preamplifiers, while JFETs provide superior input impedance and lower gate leakage for sensor interfaces. The datasheet is your primary tool: examine the hFE versus Ic curves to ensure current gain remains adequate across your operating range, noting that hFE drops at both very low and very high currents. Study capacitance versus Vce plots to verify that Cob (output capacitance) won’t limit bandwidth or cause Miller multiplication at your target frequency. Pay close attention to Safe Operating Area (SOA) graphs, which define the voltage-current boundaries for reliable operation, and verify that worst-case dissipation stays below the thermal derating curve. Source components exclusively from reputable distributors with full traceability and authenticity guarantees—counterfeit transistors with falsified specifications are a genuine threat that can invalidate your entire design effort. Platforms like Utsource provide access to verified electronic components with comprehensive datasheets and quality certifications, which is particularly valuable when sourcing components for automation accessories and industrial control applications. Cross-reference multiple datasheets when evaluating alternatives, and always design with margin: if your circuit needs 200 MHz bandwidth, select a transistor with fT exceeding 1 GHz to maintain phase margin and prevent instability.

Practical Design Tips for Robust and Stable Circuits

Achieving robust small signal transistor circuits demands systematic application of proven stabilization techniques. Implement negative feedback through emitter or source degeneration resistors—a 100Ω to 1kΩ emitter resistor in BJT stages reduces gain slightly but dramatically improves linearity, stabilizes bias against temperature drift, and increases input impedance. For multistage amplifiers, apply global feedback around the entire chain to control overall gain and bandwidth while suppressing distortion. Decoupling is non-negotiable: place 0.1µF ceramic capacitors within 5mm of each transistor’s power pin to suppress high-frequency noise, supplemented by 10µF electrolytics for low-frequency stability. Design for worst-case scenarios by analyzing circuit behavior across the full hFE range specified in datasheets—if hFE varies from 100 to 400, your bias network must maintain stable operation at both extremes. Even devices dissipating 300mW benefit from thermal management: attach small heatsinks or use copper pour on PCBs to reduce junction temperature by 20–30°C, preventing thermal drift. Prototype methodically by building one stage at a time, measuring DC bias points before applying signals, then sweeping frequency response to verify bandwidth and detect parasitic oscillations early. Use oscilloscopes to monitor waveforms at each node, confirming clean amplification without ringing or distortion that indicates instability requiring immediate compensation adjustments.

Step-by-Step Design Checklist to Prevent Errors

Follow this systematic seven-step checklist to eliminate common design errors and ensure first-pass success. Step 1: Requirement Specification—document maximum voltage, current, frequency range, gain, input/output impedance, noise budget, and operating temperature range before touching a schematic. Step 2: Transistor Type Selection—choose BJTs for low-noise audio and high transconductance applications; select JFETs for high input impedance sensor interfaces; consider MOSFETs only when switching speed or gate drive simplicity outweighs noise concerns. Step 3: DC Bias Point Calculation & Simulation—calculate quiescent collector current to position operation mid-range on load lines, use SPICE to verify stability across hFE min/max extremes and temperature from -40°C to +85°C, ensuring at least 2V headroom from saturation and cutoff. Step 4: AC Analysis & Stability Check—perform frequency sweeps to confirm bandwidth meets requirements with 45° phase margin minimum, add compensation capacitors if Miller effect causes peaking, and verify open-loop gain crosses unity before phase reaches -180°. Step 5: Thermal & Power Dissipation Review—calculate worst-case power as Vce × Ic, apply 50% derating, verify junction temperature stays below 100°C using thermal resistance calculations, and add heatsinks or copper pour when dissipation exceeds 250mW. Step 6: PCB Layout Considerations—keep base and gate traces under 10mm to minimize parasitic inductance, use star grounding to prevent ground loops, place decoupling capacitors immediately adjacent to collector/drain pins, and separate analog ground planes from digital noise sources. Step 7: Build and Test Protocol—measure DC voltages at all nodes first to confirm bias before applying signals, sweep input frequency while monitoring output on an oscilloscope for distortion or ringing, and stress-test across supply voltage and temperature extremes to validate margins.

Achieving First-Pass Success Through Systematic Design

Preventing errors in small signal transistor circuit design requires a disciplined integration of fundamental theory, precise component selection, and methodical design execution. The margin between a high-performance amplifier and an oscillating, distorted failure is often measured in millivolts of bias shift or picofarads of uncompensated capacitance. By systematically addressing biasing stability, frequency compensation, thermal management, impedance matching, and layout parasitics, you transform potential failure points into robust, predictable circuit behavior. Sourcing authentic components from verified suppliers eliminates the hidden risk of counterfeit parts that can invalidate even the most careful analysis. The seven-step checklist provided here is not merely a suggestion but a proven workflow that catches errors before they reach hardware, saving weeks of debugging and costly redesigns. Integrate these practices into your standard design process—from initial specification through final validation—and you will consistently achieve first-pass success, delivering circuits that meet performance targets reliably across production volumes and environmental extremes. The investment in rigorous design methodology pays dividends in reduced development time, lower failure rates, and enhanced professional reputation.